What Charlie Kirk Got Right — And Wrong — About His Love For The Jewish Sabbath

(ANALYSIS) Charlie Kirk isn’t wrong about Shabbat — he just has some funny ideas about what it should be.

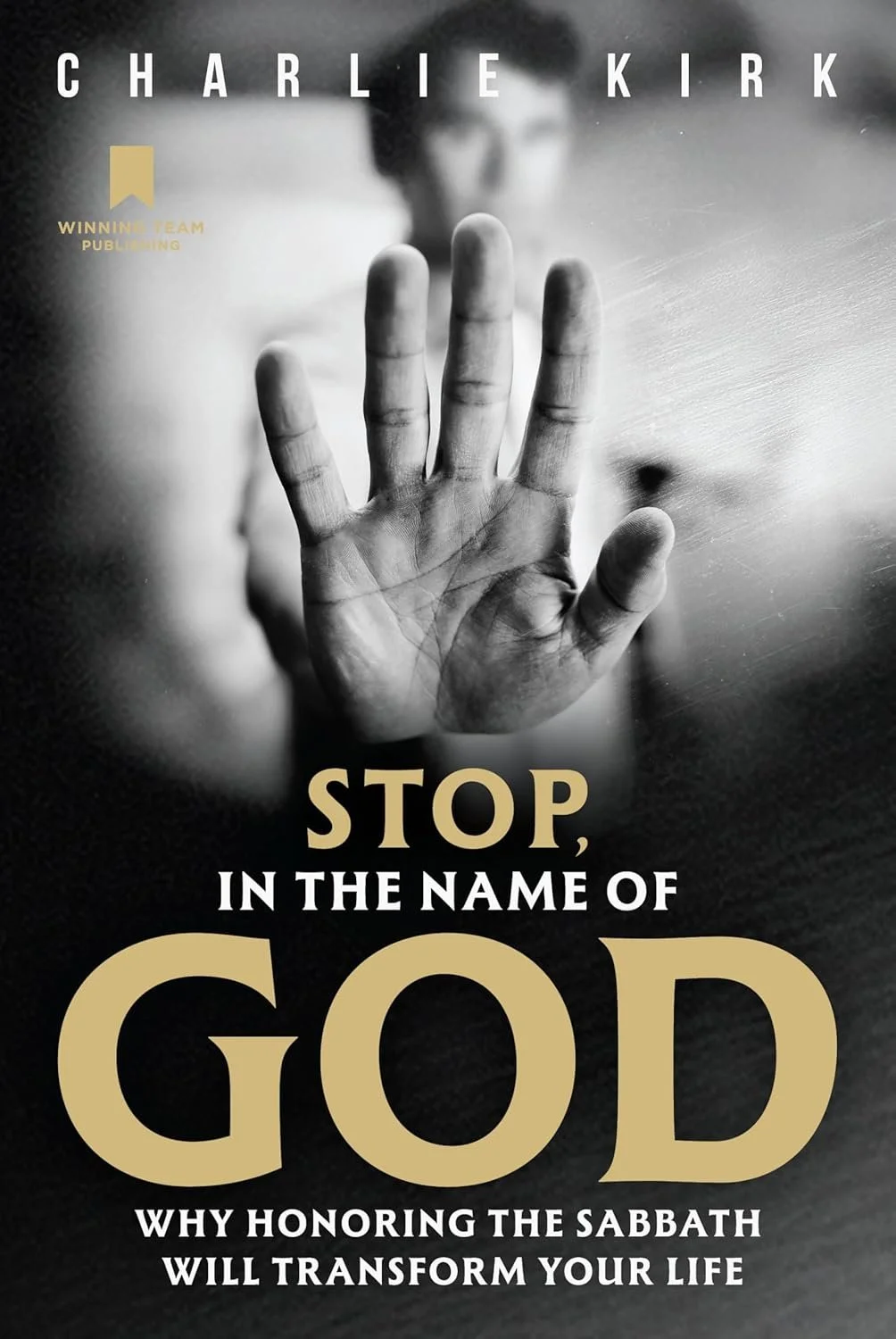

In the conservative influencer’s new book, “Stop, in the Name of God: Why Honoring the Sabbath Will Transform Your Life,” released following his assassination in September 2025 and instantly sold out on Amazon, the outspokenly devout Christian describes the day of rest adoringly.

It’s a “gift,” a taste of redemption, a break from the incessant noise of the news cycle and workday. It’s a time to connect with family and the single most important sign of God’s covenant with humanity.

These are all ideas straight out of Jewish thought. And, indeed, Kirk quotes from “The Sabbath,” by Jewish luminary Abraham Joshua Heschel, in nearly every chapter, often multiple times, while sprinkling in and other thinkers like Jonathan Sacks and Viktor Frankl.

Book cover courtesy of Winning Team Publishing

But for many Christians — Kirk was a devout evangelical, and he was clearly writing for a similar audience — whether to observe a strict Sabbath is the subject of a lively debate.

Foundational to Christianity is the idea that the coming of Jesus as messiah rendered God’s ceremonial laws — rules around food, behavior and temple sacrifice — obsolete and created a new order in which the Sabbath resides “in the heart,” rather than existing as a literal day of rest where you turn your phone off and cease work of any kind.

“Let no one act as your judge in regard to food or drink or in respect to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath day – things which are a mere shadow of what is to come; but the substance belongs to Christ,” said Paul in Colossians.

This idea has been understood by most Christians to mean that Jesus erased the need for Shabbat; instead, every day should be like Shabbat. (“Christ has set us free for something better: namely, the pursuit of holiness and fellowship with the living God as a daily lifestyle,” writes Focus on the Family in an article on the topic).

Kirk, however, disagreed; he began observing Shabbat four years before his death — specifically as a Saturday Shabbat, not the Sunday rest more common in Christianity. “Stop in the Name of God” is both an explanation of why he did so and an argument for why everyone else should do the same.

And yet the book is less a simple paean to a core Jewish ritual and more a tortured argument for how Christians can reconcile a deep suspicion of Judaism while reaping the benefits of marking Shabbat — mixed in alongside the political grievances that Kirk is best known for: opposition to the pandemic lockdown and vaccines, exhortations to traditional gender roles and, most importantly, advocacy for a Christian nationalist vision of the U.S.

Just how Jewish is Shabbat?

Kirk clearly did his research. As he makes his case for Shabbat, he leans heavily into commentaries from Heschel, Frankl and Sacks along with Christian theologians including Martin Luther and John Wesley.

While Kirk makes a case for taking a day off each week on its practical merits (better sleep, better focus, lower blood pressure), most of his argument is rooted in religion; in addition to commentaries, he quotes heavily from the Bible itself to argue that a day of rest is a Christian requirement. He digs into the deeper theological implications of Shabbat framing it as a mirror of God’s own rest in Genesis.

Noting that, biblically, Shabbat applies not only to the Israelites, but also to their animals and their workers — an element of Jewish law many readers are likely unaware of — he reads the day as a symbol of freedom. He even proposes that the fact that Shabbat applies equally to all makes it the foundation of all morality, a surprising point from someone who was outspoken about his negative views of a wide array of minority groups.

This vision of Shabbat is deeply Jewish, as are many of the interpretations Kirk borrows, and he clearly has an appreciation for the Jewish rituals. The Shabbat meal “is not dinner. It is liturgy,” he writes. “Eating becomes an act of worship.” Though he says he knows readers might view prohibitions against electricity or cooking on Shabbat as “burdens,” he argues instead that they are “scaffolding for sacred life” that “create space for joy to flourish undisturbed.”

Kirk comes across as almost envious of Orthodox Judaism.

But he can’t stay in this mode of admiration, because he isn’t speaking to Jews; his main audience is conservative Christians. And for them, Kirk has to address a specific controversy rife with antisemitic undertones: Christians believe that Jesus, as the messiah, fulfilled all of God’s ceremonial laws and rendered them irrelevant, forming a new covenant that requires only having faith in Jesus and living a broadly moral life.

That means anyone — especially Jews — who still follows them is engaging in “legalism,” a term that carries a pejorative tone in Christianity.

“Observance of a weekly day of worship, whether it be Sunday, Saturday, or any other day, should never be allowed to become a matter of religious legalism,” is how Focus on the Family put it; the emphasis is theirs.

The gist of this argument is that anyone adhering to the biblical laws fulfilled by Jesus is following a false religion, nit-picking specifics instead of leaning into devotion. Kirk’s attempt to reconcile this contradiction — respecting Shabbat without falling into dreaded “legalism” — characterizes the book.

Kirk writes in his opening chapter that the Christian God is his “ultimate authority” but he recognizes “not everyone who reads this book shares this belief and I deeply respect that.” In the very next paragraph, however, he writes that “the Bible has built the West and it is the Bible that will ultimately guide and restore it.”

This tendency to proclaim respect only to immediately undermine himself is repeated throughout the book, particularly when he discusses Judaism. Despite his clear love of the Jewish Shabbat, he cannot help but reject it because it’s not Christian. And this is key to his argument:

At its roots, Kirk’s praise of Shabbat is more concerned with convincing his readers to embrace Christianity than it is with learning from Judaism. It is only Christianity, he writes, “that can heal the divisions of our age and restore meaning to a world desperately in need of it.”

Kirk can only endorse Shabbat — for himself and for his audience — if he can prove it’s Christian, and he devotes two entire chapters to making this case, taking pains to prove that his understanding of Shabbat is free of the sin of “Judaizing.” Jesus, he writes, is “the Lord of the Sabbath” who “invites us not to legalism or laziness — but to life.” He promises that, though “the Pharisees had turned it into a crushing yoke,” Jesus’ Sabbath is not “legalism — it is liberation.”

In doing so, he reinforces the idea that Judaism is, in some way, evil, immoral and a false religion. For all his admiration toward Jewish practices, he agrees with his more skeptical co-religionists that Judaism must be exorcised from Shabbat if Christians are to observe the practice.

This discomfort with Judaism is perhaps best summarized in one, strange choice.

Though the book quotes generously from Heschel’s The Sabbath, Kirk’s prime example of the benefits of Shabbat observance comes not from Orthodox Jews, but from Seventh-Day Adventists — a small Christian movement that strictly abstain from work on the Saturday Sabbath.

He waxes poetic about their “unique behavior patterns” that include “device-free” prayer and meals in the home. “Their weekly withdrawal from the world’s pace is not escapism — it is resistance,” he writes. “It is prophetic.”

Of course, they’re not the only group to do observe a Sabbath in this way — but Kirk seems more comfortable making his case for Shabbat’s benefits using a Christian group than he does praising Jews.

The point of a Christian Shabbat

It’s no great shock that Kirk spends much of the book arguing for the primacy of Christianity.

For all his proclamations that Shabbat is for everyone — and that his argument is neither religious nor political — Kirk was famous for participating in contentious debates on exactly those topics, and can’t help but turn to them even in a book about the day of rest. He spends time not just on Judaism, but on a multitude of what he considers to be liberal enemies of Christianity.

In the introduction, Kirk includes a rant about Joe Biden, a tirade against the pandemic lockdowns and a series of boastful descriptions of his own success. He notes that he is a busy man running three different companies with 300 people on payroll, emphasizes his essential ability to fundraise millions of dollars and touts his close relationship with President Trump.

The chapters go on to offer a questionably scientific defense of creationism, a rant against materialism (and selfies), and several critiques of what Kirk believes are “false religions.” This last point, which crops up in multiple chapters, serves as an opportunity to bash Greta Thunberg, who Kirk accuses of leading an idolatrous cult of nature worship; Anthony Fauci, who is the figurehead of what Kirk calls “scientism”; and a meandering rant against Herbert Marcuse, one of the figures of the Frankfurt School, a fairly esoteric school of philosophy that Kirk blames for “woke” ideology.

None of these things have any obvious connection to Shabbat, and Kirk doesn’t attempt to make much of one. Still, their inclusion in a book ostensibly tied to a Jewish practice is revealing. An increasing number of Christians are adopting Jewish practices — not only Shabbat, but Passover Seders, wearing tallits and blowing shofars.

Yet however philosemitic these practices may appear, “Stop in the Name of God” demonstrates how comfortably they coexist with an antisemitic worldview that places Christianity above all else. Kirk’s argument for Shabbat is less about an appreciation for Jewish practice than a final entry in his life’s work advocating for a United States ruled by biblical values.

The book is less about Shabbat than it is about Christianity. Ultimately, Kirk argues that all other religions are evil, morality cannot exist without God and that Western civilization will fall if it does not obey the Bible.

That’s not to say there isn’t real appreciation for Jewish practice woven into the book. But Kirk bends the meaning of Shabbat to his real mission: Christian nationalism.

This story was originally published in the Forward. Click here to get the Forward’s free email newsletters delivered to your inbox.

Mira Fox is a reporter at the Forward. Get in touch at fox@forward.com or on Twitter @miraefox.